Richard Morris

Group Head of Expert Witness Services – Time

Group Head of Expert Witness Services – Time

‘Disruption’ and ‘delay’ are two terms that are regularly used in the same breath as they often flow from the same event. But you can have delay without disruption and vice versa as we will see later in this article.

Delay events may not necessarily have a direct impact on the critical path or delay damages but just affect individual activities.

However, disruption, unlike delay, has a direct consequence on financial loss. Therefore a disruption analysis should not be confined to events that are on the project’s critical path.

The Society of Construction Law (“SCL”) Delay and Disruption Protocol (2nd edition , p9) defines disruption as:

“… disturbance, hinderance or interruption to a Contractor’s normal working methods, resulting in lower productivity or efficiency in the execution of particular work activities.”

Disruption requires the demonstration of entitlement, causation and damages. It’s easier to prove delay – which is a matter of fact – than to demonstrate disruption.

Demonstrating disruption is more of an art than a science, however there are guidelines and procedures to follow for an analysis to be acceptable and effective.

Extensive and detailed records are a key requirement for a successful claim for disruption.

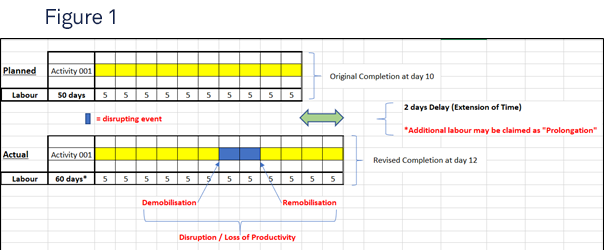

If there is only one activity and that activity is delayed by the procuring party, then under most forms of contract the delay to the activity may be claimable as an extension of time and any delay costs may be recoverable as well. (See Figure 1).

However, there remains a cost in demobilising and remobilising the labour working on the activity and this will be the disruption cost.

Over this single activity the disruption is easy to identify, however, where multiple activities are affected, the disruption costs become more difficult to establish and measure.

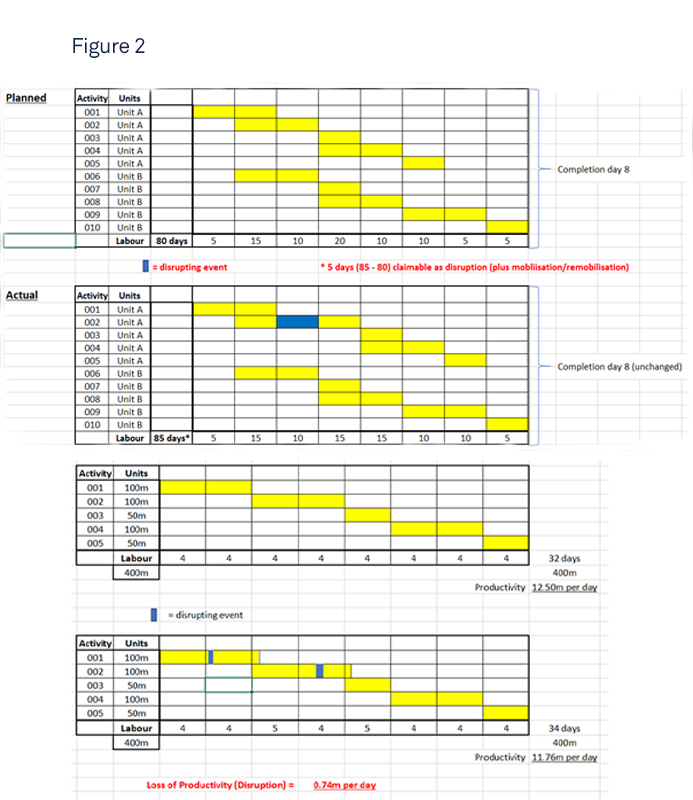

Where several events which affect the progress of the works are disrupted the impact of any one event may not be discernible from the impact of another event. (See Figure 2)

Disruption is not a cause of action at law in its own right and the contractor must explain the legal basis of entitlement. Most standard forms of contract do not address recovery for disruption but may give entitlement to claim some of the events that could lead to it in the form of loss and expense or damages.

When it comes to explaining the cause of reimbursable disruption, contractors often rely upon multiple and intermingled events to explain loss of productivity and entitlement.

Once those items that can be dealt with in isolation have been quantified, it may be acceptable to deal with the remaining disruption globally. However, the bar for acceptance of a global claim is very high and therefore carries significant risks.

Core Statement 15 of the SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol states:

“The Contractor has a general duty to mitigate the effect on its works of Employer Risk Events. Subject to express contract wording or agreement to the contrary, the duty to mitigate does not extend to requiring the Contractor to add extra resources or to work outside its planned working hours.”

Under English Law, an injured party cannot recover damages for any loss which could have been avoided by taking reasonable steps, but the onus is on the defendant to prove any failure to mitigate.

The object of acceleration is to reduce the time taken to carry out a task or a series of tasks usually with a view to mitigate a delay that has occurred or likely to occur.

There are two principal types of acceleration, express and constructive.

“The Contractor has a general duty to mitigate the effect on its works of Employer Risk Events."

Where an employer risk event delays a project but the employer still wishes to complete the project by the original date for completion and gives an instruction to accelerate – where permissible under the contract – the measures to be taken and the basis of payment should be agreed beforehand.

Core Statement 16 of the SCL Delay and Disruption Protocol continues:

“Where the Contractor is considering implementing acceleration measures to avoid the risk of liquidated damages as a result of not receiving an EOT that it considers is due, and then pursuing a constructive acceleration claim, the Contractor should first take steps to have the dispute or difference about entitlement to an EOT resolved in accordance with the contract dispute resolution provisions.”

As there is no prior agreement or instruction for this type of acceleration, the contractor places itself at risk when taking such measures, so before instigation the contractor should give notice to the employer of those measures and issue a revised programme.

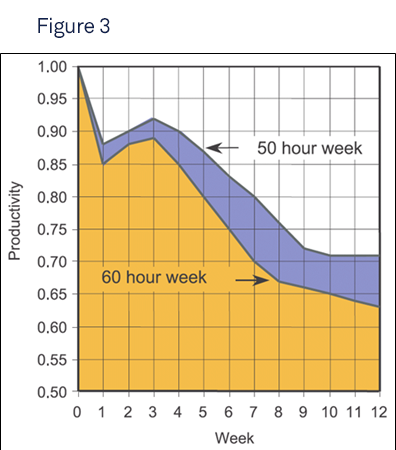

Methods of acceleration include the increase of resources (number and hours), but note that a Business Roundtable Report from November 1980 entitled “Scheduled Overtime Effect on Construction Projects” has key findings including this:

“Where a work schedule of 60 or more hours per week is continued longer than about two months, the cumulative effect of decreased productivity will cause a delay in the completion date beyond that which could have been realized with the same crew size on a 40-hour week.”

This is shown on the following graph (Figure 3) plotting output against time which shows that a productivity rate of 65% in relation to a 60 hour worked week (i.e. the equivalent of a 40 hour week) is reached after only 10 weeks.

This article is the first of a 2 part series written by Richard Morris. The next part will be focusing on how to demonstrate disruption.

To keep updated on our latest thoughts and to read the second part, please click here.